“People get tremendous anxiety and depression and you have suicide over things like this, when you have a terrible economy, you have death…definitely in far greater numbers than we’re talking about with regard to the virus.”

White House press conference, 23rd March 2020, US President Donald Trump

In recent days, US President Donald Trump has repeatedly argued that the economic consequences of public health measures to limit the spread of Covid-19 could result in more deaths, due to suicide, than the virus itself. Existing scientific evidence does not, however, support this claim.

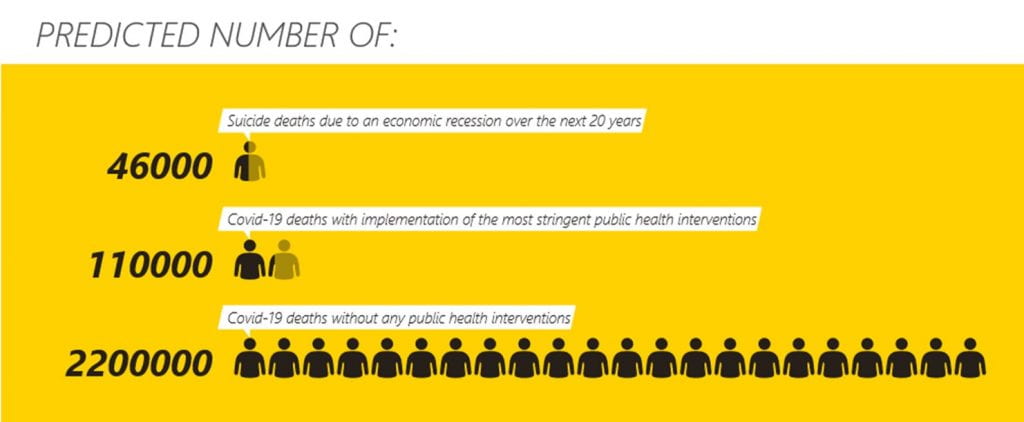

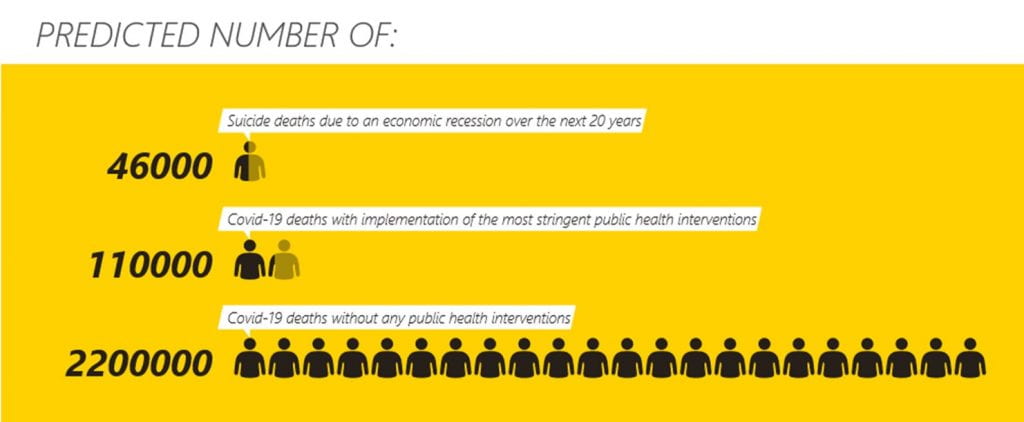

It is important to consider the impact that both the Covid-19 outbreak and related public health interventions will have on mental health, mental healthcare, and suicide rates. However, if no public health measures are implemented, the predicted number of Covid-19 deaths in the US over four months is nearly 500 times greater than the number of suicide deaths occurring between 2007-2010 attributable to the 2008 economic recession. The 2008 economic recession would have to last over 1,300 years, for the number of resultant suicide deaths to surpass the number of lives saved by stringent public health measures. Furthermore, evidence indicates the number of suicide deaths can be reduced with employment support measures and historically, in the US, the total number of deaths in the population falls during periods of recession.

Estimated number of suicide deaths in relation to economic recession

In the US between 2007-2010, there were on average 35,850 suicide deaths annually. An estimated 4,750 of these suicide deaths were attributed to the economic recession. Unemployment is a key mechanism through which economic recessions can contribute to increased suicide rates; the increase in unemployment from 5.8% to 9.6% post-recession (2007-2010) was associated with approximately 1,330 of the suicide deaths.

Estimated number of Covid-19 deaths without public health interventions

A key study, which modelled the impact of non-pharmaceutical measures, and led to a change in UK strategy, indicated that without any public health interventions or changes in individual behaviour there would be approximately 2.2 million deaths in the US due to Covid-19. The figures are based on age-stratified infection fatality ratio, ranging from 0.002% among 0- to 9-year olds and 9.3% for those aged ≥80. Most of the deaths are predicted to occur over approximately a four-month period, and around half would be due to healthcare services exceeding their capacity to treat everyone with the infection. In addition, indirect deaths may also occur as a result of over-stretched services. For example, previously treatable heart attacks may now result in death if cardiac care facilities are unavailable. As such, the number of Covid-19-related deaths would be far higher.

A key study, which modelled the impact of non-pharmaceutical measures, and led to a change in UK strategy, indicated that without any public health interventions or changes in individual behaviour there would be approximately 2.2 million deaths in the US due to Covid-19. The figures are based on age-stratified infection fatality ratio, ranging from 0.002% among 0- to 9-year olds and 9.3% for those aged ≥80. Most of the deaths are predicted to occur over approximately a four-month period, and around half would be due to healthcare services exceeding their capacity to treat everyone with the infection. In addition, indirect deaths may also occur as a result of over-stretched services. For example, previously treatable heart attacks may now result in death if cardiac care facilities are unavailable. As such, the number of Covid-19-related deaths would be far higher.

Estimated number of Covid-19 deaths with public health interventions

In the UK, case isolation, home quarantine, and social distancing are predicted to reduce the number of deaths that would have occurred with no measures in place (510,000) to approximately 90,000 (an 82% reduction), while adding school and university closure could reduce the number of deaths to around 24,000 (a 95% reduction). These calculations are based on a reproduction number of 2.4 and the triggering of social distancing and closure of educational settings when more than 200 new Covid-19 cases are diagnosed in intensive care units weekly. A similar percentage reduction in the US would equate to around 396,000 or 110,000 deaths respectively.

The wider context

Despite the implementation of a lockdown in Italy, over a six-week period the number of deaths from Covid-19 has far exceeded the 290 excess suicide attempts and deaths that occurred post-recession (2007-2010) as well as the 4,886 total suicide deaths recorded in 2016, the most recent year for which data are available.

A US economic recession may occur irrespective of whether strict public health measures are implemented, although the extent of the recession will likely vary dependent on approach taken. Economic recessions may be associated with a higher prevalence of mental health conditions and cuts to mental health services. In addition to a recession, there may be other mechanisms such as social isolation, by which strict public health measures contribute to increased mortality. Yet, to surpass the number of lives saved from reduced spread of Covid-19, these additional mechanisms would need to contribute to an extra 1.8 million suicide deaths on top of the number of suicides attributed to the 2008 economic recession. This is 40 times more deaths than the annual number of suicide deaths in the US.

Importantly, in contrast to rises in suicide rates, all-cause mortality decreased in the US during both the 2008 economic recession and the Great Depression (1930-33), for example due to shifts in trends in cardiovascular deaths and road traffic accidents. There is also evidence that the effect of unemployment on suicides can be reduced with more generous employment support measures (1,2,3).

There is no doubt that the impact on mental health and risk of suicide for populations, healthcare workers, individuals and their families as a consequence of the Covid-19 outbreak will be profound. It is a situation that could be worsened by a lack of appropriate, albeit extreme, mitigation measures. However, scientific evidence demonstrates that public health interventions to reduce the spread of Covid-19 should not be withheld on the basis that a resultant economic recession would cause more deaths by suicide.

Prianka Padmanathan is a MRC MARC PhD clinical fellow at the department of Population Health Sciences @_prianka_

Dee Knipe is a Vice Chancellor’s Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the Department of Population Health Science, University of Bristol @dee_knipe

David Gunnell is Professor of Epidemiology in the Department of Population Health Science, University of Bristol. His research expertise include the effect of the 2008 economic recession on suicide rates (1, 2, 3).

Jacks Bennett is a Bristol doctoral researcher at looking at student mental health and wellbeing @JacksBennett

Group Twitter: @SASHBristol

If you or anyone you know is affected by the issues covered in this blog, you can contact the Samaritans for free from any telephone on 116 123 in the UK. Alternatively you can email jo@samaritans.org for details of your nearest branch, where you can talk to one of their trained volunteers face to face. The International Association for Suicide Prevention (IASP) has details of support organisations in other countries.

Congratulations to Lizzy Winstone whose paper ‘Adolescent social media user types and their mental health and well-being, results from a longitudinal survey of 13 to 14-year-olds in the United Kingdom’ was among the top 10 most downloaded papers in JCPP Advances in 2022.

Congratulations to Lizzy Winstone whose paper ‘Adolescent social media user types and their mental health and well-being, results from a longitudinal survey of 13 to 14-year-olds in the United Kingdom’ was among the top 10 most downloaded papers in JCPP Advances in 2022.