By Professor David Gunnell

In the last 18 months, Bristol has been in the eye of a storm of concern about student mental health following the tragic deaths by suicide of a number of our students.

First and foremost our thoughts are with the families and friends of all those who have lost a loved one. They will quite rightly want to know what could have been done to prevent each death. It will be important that lessons are learnt and widely shared across the university sector.

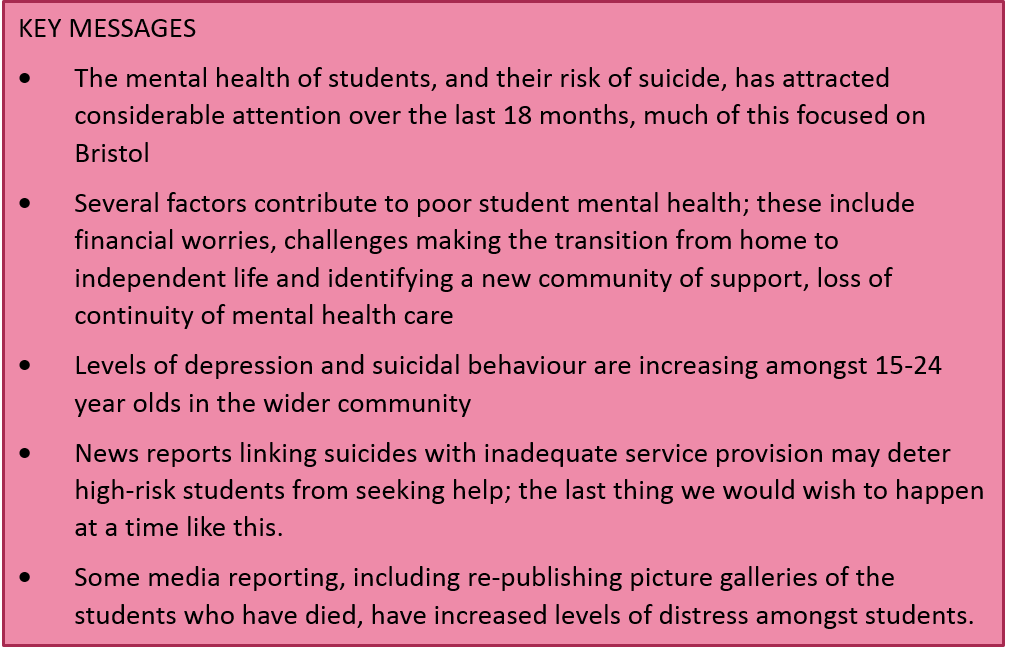

What do we know about the mental health of the UK’s 2.3 million students and what lies behind the recent tragic deaths? It is widely recognised that levels of depression and self-harm in young people are increasing in the UK and internationally. UUK’s recent analysis highlighted a six-fold rise in the number of UK students disclosing a mental health condition to their university since 2007. Data recently presented to the National Suicide Prevention Advisory Group show rises in suicides in 15-19 year olds in England. The rises in levels of distress seen by UK universities likely mirror those seen in the wider population of this age. There are several possible additional contributors to student mental health problems. These include:

- Concerns about the high levels of debt students incur because of course fees in excess of £9,000, in addition to their costs of living. This increases the pressure to perform well at university

- Difficulties establishing new friendship groups and support networks as they transition to a new geographic location after leaving home for the first time

- Loss of continuity of medical and mental health care for those previously under specialist care for mental health conditions in their home town

- Loss of the sense of community provided by friends, families and schools, with students being increasingly able to access course materials on-line and so avoid attending lectures. Furthermore, pressures on university finances have resulted in larger year-group sizes and an associated sense of anonymity. When I studied medicine at Bristol in the 1980s my year group size was 120; now it is closer to 300.

Concern about student suicide and mental health dates back at least to the 1950s, following the identification of a high incidence of suicide amongst Oxford undergraduates. In 2015-16 York University was the focus of similar concerns and informal conversations with colleagues elsewhere in the UK points to similar worries about student suicides.

The research literature highlights “clusters” of student suicide deaths in the USA and elsewhere around the world. Such clusters have also been reported in secondary schools and communities.

We don’t know what causes these clusters. Psychological theories suggest risk may “spread” by social contagion, social learning, suggestion or imitation. But research such as Madelyn Gould’s elegant analysis of clusters in the USA tells us clusters are more common in young people and may be precipitated by news reporting. Reporting practices were recently criticised in relation to another UK cluster. For this reason Public Health England’s guidance for media reporting in relation to suicide clusters makes 10 recommendations (see page 24); these include:

- avoid re-running details of each death in every report, re-reporting previous stories and making links to other suicides

- do not give undue prominence to a story, such as front cover splash and dramatic headlines and use of photographs and memorials of people who have died – specifically repeated use of image galleries should be avoided

Whilst most news organisations, including our student news groups, have followed this guidance, several, most recently the Sun (Saturday May 19th) have not. Some media organisations have repeatedly published picture galleries of the students who have died, taken in happier times, each time a further death has occurred. These may re-trigger grief in family and friends recovering from their loss. They may make other students feel vulnerable – “if this happy looking person took their own life, then am I too at risk?” It is possible that news coverage may have contributed to some deaths.

Research suggests that the proportion of students experiencing suicidal thoughts in a 12 month period is around 17%, and 9% have made suicide plans. If these thoughts and plans occur in an environment where models of people taking their lives in similar situations exist, suicide may become a more tenable option.

Furthermore, news reports linking the suicides with long waiting times for support and inadequate service provision, whilst rightly shining a light on important challenges across the university sector, may also deter people from seeking help, the last thing we wish to happen at times like this.

The impact of the deaths on students is exemplified by the 60% increase in referrals for counselling following deaths in Bristol in 2017. These will reflect both heightened concerns amongst students themselves as well as the staff they interact with.

Support, administrative, teaching and other academic staff too are profoundly affected by the death of a student in their care.

These are tough times for young people and universities. We need to better understand the most effective approaches to improving student mental health and support those experiencing difficulties, as well as learn lessons from the recent deaths. Furthermore, we need to understand the drivers behind recent rises in young people’s distress to inform prevention. We also need to review reporting guidance. Perhaps it is time the Independent Press Standards Organisation’s (IPSO) code of practice for reporting on suicide deaths is extended to include avoiding repeatedly publishing pictures of those who have died.

David Gunnell is Professor of Epidemiology in the Department of Population Health Science, University of Bristol. He has a long-standing research and policy interest in the epidemiology and prevention of suicide in the UK and internationally.

You can follow @SASHBristol on Twitter.

If you or anyone you know is affected by the issues covered in this blog, you can contact the Samaritans for free from any telephone on 116 123 in the UK. Alternatively you can email jo@samaritans.org for details of your nearest branch, where you can talk to one of their trained volunteers face to face. The International Association for Suicide Prevention (IASP) has details of support organisations in other countries.